With all the BoingBoing data from the past ten years now in Fluidinfo the next question is “what can we do with it..?”. That’s what I’ll be answering in this technical how-to, so expect lots of code / examples!

I’ve organised the article into four parts:

- Basic Fluidinfo concepts

- How BoingBoing data is organised

- Minecraft (example data mining interactions with the API)

- Super-duper cool stuff (this is the best bit!)

Basic Fluidinfo Concepts

Understanding Fluidinfo involves four simple concepts:

- Objects represent things.

- Tags define objects’ attributes.

- Namespaces organise tags.

- Permissions apply to namespaces and tags.

How does this all fit together..? Objects are simply tagged with data. Put another way, tags associate a value with an object.

The other important concept to make clear is that nobody owns objects, there are no permissions associated with objects and objects last for ever. Although every object has a unique ID they are also usually identified by a globally unique and immutable “about” tag value. It’s used as you’d expect: to indicate what the object is supposed to be about. Finally, anyone can add data to any object (more on this later).

(er… that’s really all it is.)

Of course, since Fluidinfo is a data-store it is possible to do searches, link objects and store all sorts of different types of data (from primitive types like numbers, booleans and text to more opaque values such as images, video, sound and other binary data).

Oh yeah, interaction with the data is via a simple yet powerful REST API. There are plenty of client libraries in many different languages which allow you to work without worrying about the dirty implementation details.

How the BoingBoing data is organised in Fluidinfo

Each of the 64,000 BoingBoing articles is represented by a corresponding Fluidinfo object whose about tag value is the URL of the original post on boingboing.net. In the original XML dump, each post looked something like this:

<row>

<permalink>http://boingboing.net/2000/01/21/street-tech-reviews-.html</permalink>

<created_on>2000-01-21 14:07:38</created_on>

<basename>street_tech_reviews_</basename>

<author>Mark Frauenfelder</author>

<title>Street Tech Reviews and news</title>

<body><A HREF="http://www.streettech.com/">Street Tech</A> Reviews and news for gadget-lovers and propeller heads of all stripes.</body>

<body_more>NULL</body_more>

<comment_count>0</comment_count>

<categories>NULL</categories>

</row>

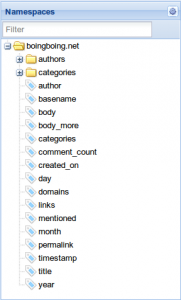

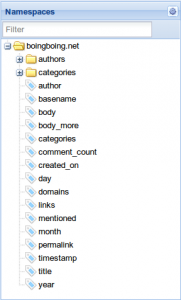

I’ve done the simplest thing possible: created a top-level boingboing.net namespace in Fluidinfo under which all tags used to annotate BoingBoing data are defined. I’ve added tags to this namespace that map to the original XML elements: permalink, created_on, basename, author, title, body, body_more, comment_count and categories. The Fluidinfo objects representing BoingBoing posts have data associated with them using these tags. For example, the object representing the post described in the XML example above has a boingboing.net/title tag with the associated value: “Street Tech Reviews and news”.

Since I was also cleaning the raw XML I decided to extract / re-structure some of the data. This resulted in some additional tags: year, month, day, timestamp, links and domains. The function of the date related tags should be clear. The links and domains tags are interesting because I scraped all the anchor tags in the body and body_more fields and processed the href values. Obviously the links tag references a list of all the URLs referenced in an article and the domains tag references a related list containing just the domain names.

I did one final enhancement to the data dump. I extracted all the authors and categories and turned them into tags. When I imported the data I used these tags in the “delicious” way of tagging: simply by having such a tag (with no associated value) an object is associated with an author or category.

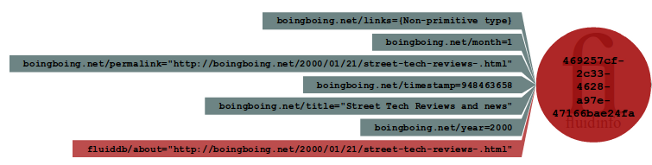

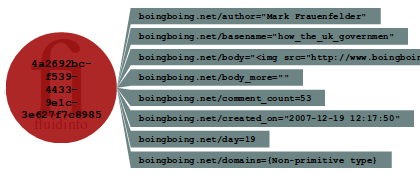

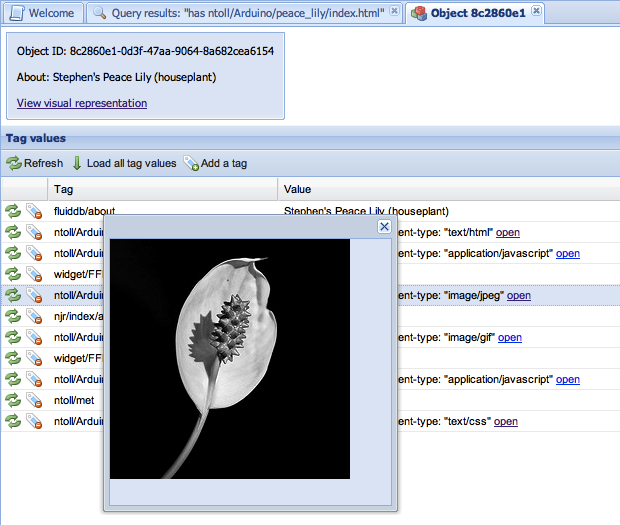

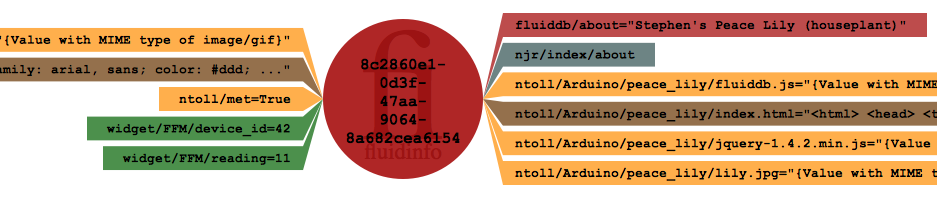

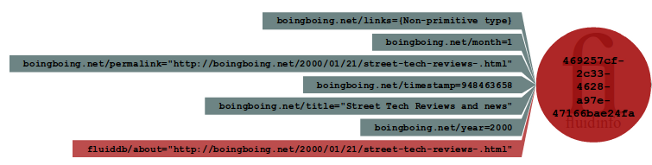

Here’s what an object representing a BoingBoing article looks like:

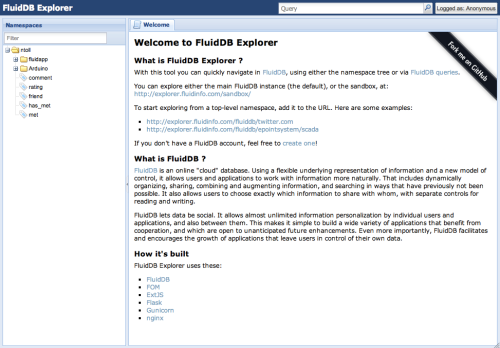

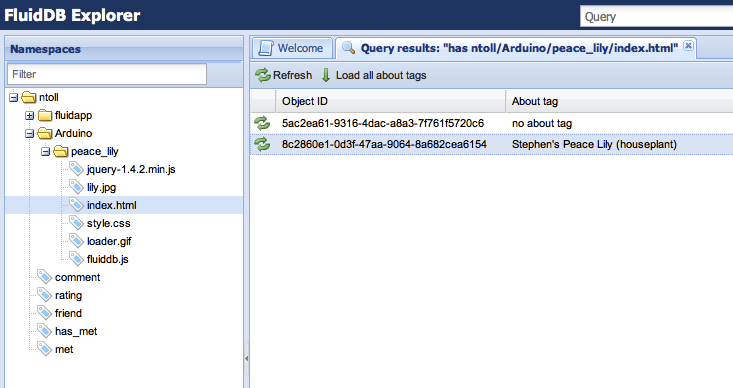

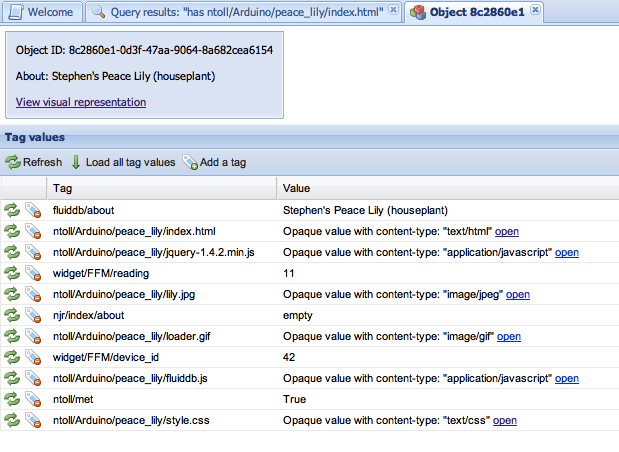

Another interesting view on the data is to explore the BoingBoing tags and namespaces in the Fluidinfo Explorer (see the screen-shot on the right). In the Explorer, if you right-click on a tag and select “Open Object” you’ll see the object that represents the tag in the main area of the application. This object is itself tagged with useful information – such as a description (containing copyright information). Yeah, I know, it sounds odd but this makes meta-tagging possible.

In addition to creating Fluidinfo objects for all the BoingBoing articles I also created an object for every domain referenced by BoingBoing throughout the last ten years.

The about tag value for these domain objects is the domain name itself. For example, there is an object about the “bbc.co.uk” domain.

Each of these domain objects has been tagged with a list of all the BoingBoing articles that mention them. This is, I think, rather cool. To continue the example, the bbc.co.uk domain was referenced in 177 BoingBoing articles.

Minecraft (example data mining interactions with the API)

So here comes the cool how-to stuff…

Should you need to, use the existing documentation to read about the Fluidinfo API in super-painfully-precise-techno-vision. However, I’m going to present a quick guided tour in the form of a Python session using the fluiddb.py module (remember my advice to use one of the client libs). The advantage of using fluiddb.py is that it’s a very thin layer on top of the HTTP API so you get a feel for how various things work. The other advantage is that reading Python is like reading pseudo-code and is thus a great teaching tool.

In the following example I simply import the fluiddb module and ask it for information about my user (ntoll). The basic pattern for calling Fluidinfo is: fluiddb.call(“HTTP-VERB“, “PATH IN API“, OTHER OPTIONAL ARGS)

>>> import fluiddb # loads the module into the session

>>> headers, body = fluiddb.call('GET', '/users/ntoll') # 'GET' is the HTTP verb & '/users/ntoll' is the API path

>>> headers # contains the HTTP headers returned from Fluidinfo

{'cache-control': 'no-cache',

'connection': 'keep-alive',

'content-length': '76',

'content-location': 'https://fluiddb.fluidinfo.com/users/ntoll',

'content-type': 'application/json',

'date': 'Tue, 08 Feb 2011 19:42:10 GMT',

'server': 'nginx/0.7.65',

'status': '200'}

>>> body # contains the actual result, in this case basic information about the user ntoll (me)

{u'id': u'a694f2d0-428e-4aaf-85d1-58e903f56b30',

u'name': u'Nicholas Tollervey'}

Notice how the “content-location” in the headers tells you what the full URL of the API call is (this is interesting since fluiddb.py creates this automagically for you). The body (result) is a Python dict object that basically mirrors the JSON dict object Fluidinfo served up.

The following example grabs information about a specific object. Notice that I pass in the path to the Fluidinfo resource I’m GETting as a list. This ensures that the BoingBoing URL gets correctly percent encoded.

>>> headers, body = fluiddb.call('GET', ['about', 'http://boingboing.net/2000/01/21/street-tech-reviews-.html']) # get basic information about the object about "http://boingboing.net/2000/01/21/street-tech-reviews-.html"

>>> headers

{'cache-control': 'no-cache',

'connection': 'keep-alive',

'content-length': '455',

'content-location': 'https://fluiddb.fluidinfo.com/about/http%3A%2F%2Fboingboing.net%2F2000%2F01%2F21%2Fstreet-tech-reviews-.html',

'content-type': 'application/json',

'date': 'Tue, 08 Feb 2011 19:45:27 GMT',

'server': 'nginx/0.7.65',

'status': '200'}

>>> body

{u'id': u'469257cf-2c33-4628-a97e-47166bae24fa',

u'tagPaths': [u'boingboing.net/timestamp',

u'fluiddb/about',

u'boingboing.net/day',

u'boingboing.net/month',

u'boingboing.net/year',

u'boingboing.net/authors/markfrauenfelder',

u'boingboing.net/comment_count',

u'boingboing.net/author',

u'boingboing.net/basename',

u'boingboing.net/body',

u'boingboing.net/domains',

u'boingboing.net/created_on',

u'boingboing.net/permalink',

u'boingboing.net/title',

u'boingboing.net/links']}

>>>

Hopefully, the result speaks for itself: it contains the unique ID of the Fluidinfo object that is about the BoingBoing URL, and a list of the tags on that object. Getting the value of a specific tag is simple:

>>> headers, body = fluiddb.call('GET', '/objects/469257cf-2c33-4628-a97e-47166bae24fa/boingboing.net/title')

>>> body

u'Street Tech Reviews and news'

I simply appended the path to the tag onto the object’s unique ID (this also works with the about tag too as used in the prior example).

Returning tag values for a set of results that match a query is also easy. The equivalent of the following SQL-esque query:

SELECT title, categories, created_on FROM boingboing.net WHERE authors="markfrauenfelder" AND year=2010;

… is:

>>> headers, body = fluiddb.call('GET', '/values', tags=['boingboing.net/title', 'boingboing.net/created_on', 'boingboing.net/categories'], query="has boingboing.net/authors/markfrauenfelder and boingboing.net/year=2010")

A call is made to the “/values” endpoint with a list of tags whose values we want returned and a query to generate the result set. The query is written in Fluidinfo’s super-simple query language. The headers of the response look like this:

>>> headers

{'cache-control': 'no-cache',

'connection': 'keep-alive',

'content-length': '287328',

'content-location': 'https://fluiddb.fluidinfo.com/values?query=has+boingboing.net%2Fauthors%2Fmarkfrauenfelder+and+boingboing.net%2Fyear%3D2010&tag=boingboing.net%2Ftitle&tag=boingboing.net%2Fcreated_on&tag=boingboing.net%2Fcategories',

'content-type': 'application/json',

'date': 'Wed, 09 Feb 2011 10:55:50 GMT',

'server': 'nginx/0.7.65',

'status': '200'}

The actual results are a JSON object (of which the following is only a fragment):

{

"results": {

"id": {

"f2976562-eba6-47e4-94a1-b36ffe9a2ab1": {

"boingboing.net/created_on": {

"value": "2010-10-14 13:14:14"

},

"boingboing.net/categories": {

"value": [

"science",

"technology",

"art and design",

"design"

]

},

"boingboing.net/title": {

"value": "TED releases iPad app today"

}

},

"627ebf2e-e38d-41da-a709-16294b4ab6f2": {

"boingboing.net/created_on": {

"value": "2010-02-19 11:29:36"

},

"boingboing.net/categories": {

"value": [

"culture"

]

},

"boingboing.net/title": {

"value": "Miniboss T-shirt in the Boing Boing Bazaar"

}

} // etc... for lots of results

}

}

}

Happily, fluiddb.py has converted it into the Python equivalent so we can find out some useful information and look at individual results.

>>> len(body['results']['id']) # how many results do we have..?

1214

>>> body['results']['id'].keys()[0] # what's the id of the first result..?

u'f2976562-eba6-47e4-94a1-b36ffe9a2ab1'

>>> body['results']['id']['f2976562-eba6-47e4-94a1-b36ffe9a2ab1'] # show the record for the first result...

{u'boingboing.net/categories': {u'value': [u'science',

u'technology',

u'art and design',

u'design']},

u'boingboing.net/created_on': {u'value': u'2010-10-14 13:14:14'},

u'boingboing.net/title': {u'value': u'TED releases iPad app today'}}

Great! So you have all the tools you need to search and explore all the BoingBoing articles from the last ten years. That’s what a conventional data API provides.

However, Fluidinfo can do additional super-duper cool stuff..!

Super-duper cool stuff!

Fluidinfo is an openly writeable database where objects have value because they are annotated with data from different sources. That’s why anyone can tag any data to any object. Since you control who can use, read and control your namespaces and tags, you still maintain control of data and importantly create a mechanism for trust.

You can trust values annotated with tags from the boingboing.net namespace because only BoingBoing is allowed to create and edit anything under this namespace. Since BoingBoing has annotated objects with information about articles then it’s safe to assume the objects are about a BoingBoing articles.

Here’s the super-duper stuff: you can contribute data to these objects too.

How..?

I’m glad you asked… 🙂

First of all you’ll need an account on Fluidinfo. Once you’ve signed up you’ll be the proud owner of a top-level namespace with the same name as your username. Before you can add data to objects you’ll need to create some tags to achieve this:

>>> fluiddb.login('ntoll', 'top-secret-password') # change as appropriate

>>> newTag = {'name': 'tuba', 'description': 'Related to Tubas in some way so it must be awesome!', 'indexed': False})

>>> headers, body = fluiddb.call('POST', '/tags/ntoll', newTag) # create new tag in /ntoll namespace

>>> headers

{'cache-control': 'no-cache',

'connection': 'keep-alive',

'content-length': '104',

'content-type': 'application/json',

'date': 'Wed, 09 Feb 2011 13:08:52 GMT',

'location': 'https://sandbox.fluidinfo.com/tags/ntoll/tuba',

'server': 'nginx/0.7.65',

'status': '201'}

>>> headers, body = fluiddb.call('GET', '/tags/ntoll/tuba', returnDescription=True)

>>> body

{u'description': u'Related to Tubas in some way so it must be awesome!',

u'id': u'b03f6937-cebf-481d-a0eb-5fd355a8a602',

u'indexed': False}

The new tag is given a name (“tuba”), description and an indication if it should be indexed. The “201” status that Fluidinfo returned confirms that the new tag was successfully created under the “ntoll” namespace.

In case you hadn’t guessed I like tubas! I’d like others to find other tuba related objects in Fluidinfo so I’ve decided I’ll attach this newly created tag to anything tuba-related, including BoingBoing posts. As it happens Fluidinfo helps me get a bunch of these posts with a search like this:

>>> headers, body = fluiddb.call('GET', '/values', tags=['boingboing.net/title', 'fluiddb/about',], query = 'fluiddb/about matches "tuba"')

>>> body

{

"results": {

"id": {

"e6c108f4-bd10-4cd3-b7d5-ad549b988c28": {

"fluiddb/about": {

"value": "http://boingboing.net/2006/06/22/flaming-tuba-guy-dav.html"

},

"boingboing.net/title": {

"value": "Flaming Tuba guy David Silverman on NBC Tonight Show 6/23"

}

},

"0c006f04-0663-48d6-9f11-4e082e75eb51": {

"fluiddb/about": {

"value": "http://boingboing.net/2010/11/22/tuba-skinny-old-time.html"

},

"boingboing.net/title": {

"value": "Tuba Skinny: Old timey blues and jazz street act from New Orleans"

}

}

}

}

}

I’ve simply queried for matches for the word “tuba” in the fluiddb/about tag. Now that I’ve got a couple of results I can tag them like so:

>>> for tubaItem in body['results']['id']:

... header, body = fluiddb.call('PUT', '/objects/%s/ntoll/tuba' % tubaItem, "Umpah-tastical, man!")

... print header['status']

'204'

'204'

Yay! I’ve added some information to a couple of objects about BoingBoing articles! Let’s just confirm this by asking Fluidinfo for all the objects tagged with ntoll/tuba:

>>> headers, body = fluiddb.call('GET', '/values', tags=['fluiddb/about', 'boingboing.net/title', 'ntoll/tuba', ], query="has ntoll/tuba")

>>> body

{

"results": {

"id": {

"e6c108f4-bd10-4cd3-b7d5-ad549b988c28": {

"ntoll/tuba": {

"value": "Umpah-tastical, man!"

},

"fluiddb/about": {

"value": "http://boingboing.net/2006/06/22/flaming-tuba-guy-dav.html"

},

"boingboing.net/title": {

"value": "Flaming Tuba guy David Silverman on NBC Tonight Show 6/23"

}

},

"0c006f04-0663-48d6-9f11-4e082e75eb51": {

"ntoll/tuba": {

"value": "Umpah-tastical, man!"

},

"fluiddb/about": {

"value": "http://boingboing.net/2010/11/22/tuba-skinny-old-time.html"

},

"boingboing.net/title": {

"value": "Tuba Skinny: Old timey blues and jazz street act from New Orleans"

}

},

"024bf1b6-348d-4839-8700-cbb30d86fb97": {

"ntoll/tuba": {

"value-type": "image/jpg",

"size": 467947

},

"fluiddb/about": {

"value": "CrossCountryTuba"

}

},

"a694f2d0-428e-4aaf-85d1-58e903f56b30": {

"ntoll/tuba": {

"value": "I play tuba!"

},

"fluiddb/about": {

"value": "Object for the user named ntoll"

}

}

}

}

}

Oops, I forgot I’d already tagged a couple of non-BoingBoing objects with the ntoll/tuba tag: one whose about tag value is “CrossCountryTuba” and the other being the object that represents me in Fluidinfo.

Notice how the value for the ntoll/tuba tag on the object about “CrossCountryTuba” contains only metadata: the type of data stored by that tag on that particular object (image/jpg) and the size of the data (467947 bytes). Looks like it’s an image of some sort. Let’s get it and see:

>>> headers, body = fluiddb.call('GET', '/objects/024bf1b6-348d-4839-8700-cbb30d86fb97/ntoll/tuba')

>>> image = open('tuba.jpg', 'w')

>>> image.write(body)

>>> image.close()

And what does tuba.jpg contain..?

Cool! Fluidinfo stores any type of data so long as you supply the appropriate MIME type when you upload the data.

How did I get the data into Fluidinfo..?

>>> tuba = open('Desktop/tuba.jpg', 'r') # open the original image

>>> header, body = fluiddb.call('PUT', '/objects/024bf1b6-348d-4839-8700-cbb30d86fb97/ntoll/tuba', tuba.read(), mime='image/jpg') # notice how I specify the MIME type

>>> tuba.close()

>>> headers['status'] # check we got a 200 OK response

'200'

>>> header, body = fluiddb.call('PUT', '/objects/024bf1b6-348d-4839-8700-cbb30d86fb97/ntoll/attribution', 'Tuba photo source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/dust/3813581130 licensed under a CC-BY 2.0 license') # need to add attribution as per the license

Simple..!

Now we’ve covered a lot of ground, so let’s just consider where we’ve got to.

- We have a consistent, simple and powerful API to play with.

- We can retrieve values using a simple query language referencing data contributed from many different users.

- We can contribute data ourselves in such a way that the data remains under our control.

- We can put all our data in the right place. If I want to contribute something about a BoingBoing article I just tag it to the object representing the right BoingBoing article.

- We can contribute all sorts of data be it searchable primitive values like numbers, text and booleans or opaque data such as images, audio or anything else for which you can specify a MIME type.

You’re armed with enough basic knowledge to both mine BoingBoing data and contribute to it too. In fact, if you look carefully you’ll find all sorts of interesting objects in Fluidinfo. Remember, to find out more about the API check out our technical documentation.

Dive in, have fun and we’re more than happy to answer questions.

Image credits: BoingBoing’s logo and font butchered with permission (thanks @mustardhamsters!), diagram generated by abouttag written by Nick Radcliffe and the “Cross Country Tuba image” is © 2009 Amanda M Hatfield under a Creative Commons license.