Image: psd

Computer scientists are fond of talking about metadata. There often seems to be an assumption that drawing a distinction between metadata and data is useful and perhaps even necessary.

At an architectural level, I think that’s entirely wrong. Any storage architecture that maintains a distinction between metadata and data has real problems that will limit its flexibility and usefulness. Note that I’m not saying that an application shouldn’t maintain a distinction between metadata and data, or that applications shouldn’t present things to users in those terms, or that it’s not useful to think in terms of metadata and data. I’m also not claiming that every storage architecture needs to be flexible – there are obviously times where that appears unnecessary (though in many cases you may end up wanting more flexibility).

I’ll simply argue that if you aim to build a storage architecture with real flexibility, maintaining a distinction between data and metadata runs directly counter to your goal. Below I’ll outline some reasons why.

But first, consider the natural world. If you talk to a regular person — meaning someone who’s not a computer scientist, a librarian, an archivist etc. — and ask them if they know what metadata is, you’ll probably draw a blank. Why is that? It’s because the distinction between data and metadata is entirely artificial. It does not exist in the real world, and it’s clear that regular people can get by just fine without it. Fluidinfo draws its inspiration from the way we work with information in the natural world, and maintains no such distinction.

It’s interesting to speculate on the origins of the metadata vs data distinction. I’d love to know its full history. I suspect that it arose from early architectural constraints, from the relative design and programming ease of maintaining a set of constant-size chunks of information about files apart from the dynamic and variable-size memory required by the contents of files. I suspect it probably also has to do with architectural limitations and the slowness of early machines.

Here then are the main reasons why the distinction is harmful.

- Two access methods: When metadata and data are stored separately, the way to get at those two different things is likely to be different. Consider inodes in a UNIX filesystem versus the disk blocks containing file data. They are stored differently and cannot be accessed in a uniform way. This causes internal complexity for the storage architecture.

- Two permissions systems: There are likely to be two permissions systems governing changes to metadata and data. This is another source of internal complexity for the architecture.

- Search across the two is complex or impossible: Why has it traditionally been so hard to find, for example, a file with “accounts” in its name and “automobiles” in the contents? Because this is a simultaneous search across file metadata and file content. The division between metadata (the name) and the data (the content) made such searches extremely difficult. Even with modern systems it’s awkward. Consider the UNIX find command which searches based on file metadata and the grep command which searches file contents. Combining the two is not easy. It’s at least possible in some systems these days, but that’s because those systems pull all the information together and build a separate index on it – i.e., they allow it by removing the division between metadata and data.

- A central piece of content: Systems, especially document or file systems, usually maintain a distinction between the content and the metadata about the content. But the real world doesn’t work that way. You may possess information about something without having the thing. There may be no pieces of content, or there may be many.

- Who decides?: If a system maintains a distinction between metadata and data, who decides which is which? Almost inevitably, it’s a programmer, a system architect, or a product manager who makes those decisions. There’s an implicit assertion that they know more about your information than you do. They decide what should be in the metadata. While there are systems that let users create metadata, they are usually limited in scope – someone has decided in advance how much metadata a regular user should be allowed to create, what kind of metadata it can be, how it will be used, how users will be allowed to search on it, etc. The intentions are good, but the whole thing smacks of parental control, of hand-holding, of “trust us, we know better than you do”.

- Time dependency at creation: Systems maintaining the distinction also introduce an unnatural time dependency. Until the content (i.e., the data) is available, there’s nowhere to put the metadata. E.g., a file object has to be created before it can have metadata, a web page has to come into existence before you can tag it. But the real world doesn’t work that way. E.g., you can have an opinion about someone you’ve never met, or someone who’s dead or fictional. You can have a summary of a call agenda before the call happens, or notes about a meeting before the minutes of the meeting are prepared.

- Time dependency at deletion: The awkward time dependency bites when the content is deleted too. The metadata necessarily vanishes because the architecture doesn’t allow it to persist: there’s literally nowhere to put it. Once again, the real world doesn’t work that way. E.g., you’re sent a large image file of someone’s pet cat – you take a look and, to show you care, make a mental note of its name and breed, but you delete the image because you don’t want to store it. Or suppose you give away or lose your copy of Moby Dick – you don’t therefore immediately forget the book’s title, its plot, the author, the name of the main character, an idea of how long it is, the book’s first line, etc. The “content” is gone, but the metadata remains. You may have never owned the book, you may think you have a copy but do not, you may have two copies – in the natural world it just doesn’t matter, and nor should it in a storage architecture. Interestingly, Amazon are currently being sued because they threw away someone’s metadata in the process of removing a copy of Orwell’s 1984 from a Kindle. You can bet the metadata was removed automatically when the content was removed.

OK, enough examples for now.

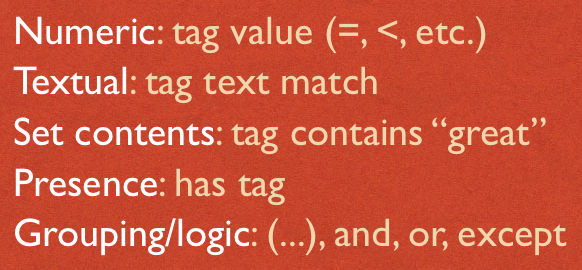

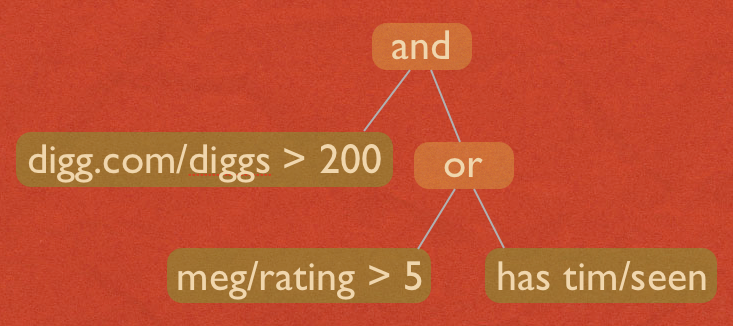

Fluidinfo has none of the problems listed above. It has absolutely no distinction between metadata and data. It has a single permissions system that mediates access to all information. When a tag (perhaps used or presented as the “content” by an application) is removed from an object, all the other tags remain. There is no distinction between important system information and the information stored by any regular user or application – they’re all on an equal footing, and that includes future applications and users. No-one gets to set the rules about what’s more important and what’s not, there’s simply no distinction. You can search on anything, using a single query language – the system uses the query language to find things it needs, just like any other application. The single permission system mediates who can do what – equally and uniformly.

I used to argue that everything should just be considered data. But I think David Weinberger puts it better in Everything is Miscellaneous where he says it’s all metadata. Call it what you will, it’s clear (to me at least) that at a fundamental level there should be no distinction.

BTW, if you’re into self-reference, you might also interested to know that Fluidinfo uses itself to implement its permissions system. Permissions are just more information, after all. Fluidinfo stores that information for tags, namespaces, and users onto the regular Fluidinfo objects that are about those things. There truly is no metadata / data distinction. It’s a little like Lisp: once you have the core system in place, you can (and should) use it to implement the wider system.