I’ve been asked what Fluidinfo is hundreds of times. I’ve never really known how to answer because it can be looked at from many different angles. As I try to answer, I often feel like I’m holding up a large opaque crystal in front of me, turning it this way and that, until I find an angle that makes sense for this particular listener. I came slowly to the realization that there is no perfect answer, and that Fluidinfo can be many things to many different people. It’s like looking through a kaleidoscope: keep turning it until you see it in a way that’s attractive.

I’ve been asked what Fluidinfo is hundreds of times. I’ve never really known how to answer because it can be looked at from many different angles. As I try to answer, I often feel like I’m holding up a large opaque crystal in front of me, turning it this way and that, until I find an angle that makes sense for this particular listener. I came slowly to the realization that there is no perfect answer, and that Fluidinfo can be many things to many different people. It’s like looking through a kaleidoscope: keep turning it until you see it in a way that’s attractive.

I’ll try to explain some of these points of view in later posts. For now, I’ll just give the flavor of some of them.

The many possible views of Fluidinfo do not mean that it is complex. It’s actually very simple. But it has a flexibility and generality that obviously make it difficult to grasp. Even when you do understand it, it’s common to be able to imagine two or three ways you might use it to solve a particular problem. I’m going to save a description of the object model for later, too.

In no particular order then, here are 10 ways of thinking about what Fluidinfo might be, or become.

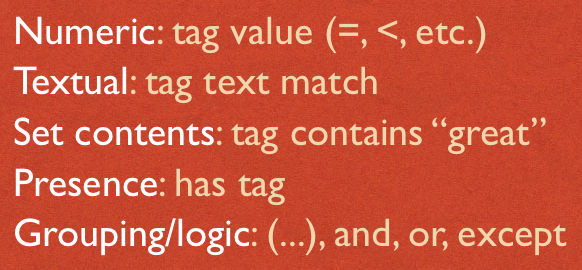

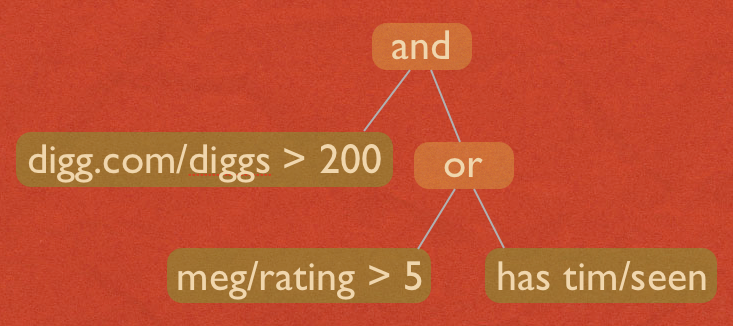

1. A database with the heart of a wiki: The wiki analogy is strong in some ways: Anyone can add data (but see below), applications can collaborate, data put in a shared place is more valuable, and abstractly there are Fluidinfo objects for every purpose just like there are wiki pages for every subject – all waiting for someone to create them. But the analogy is very poor in others: Fluidinfo has a strong permissions system that can prevent others from changing or even seeing your data, there is a query language, and content is typed. So Fluidinfo has the flavor of a wiki, but when you get right down to it almost everything is quite unlike a wiki.

There is an interesting related question here. The world of encyclopedias was tightly controlled, and very few people were allowed to write – the encyclopedia was the ultimate read-only authority. Comically, it seemed, Wikipedia was the exact opposite. Yet in the space of a few years, the unthinkable had happened: Wikipedia had eclipsed even the mighty Encyclopedia Britannica. Can Fluidinfo do for applications and traditional databases what Wikipedia did for humans and traditional encyclopedias? You don’t have the rigid tables or schema, anyone can write, content can evolve, and there is no top down control.

2. A metadata store for everyone and everything: Fluidinfo has a special about tag. You can use it to ask for the object that’s about something, like a URL or an ISBN number. That gives applications an easy shared place to put things about other things – i.e., to store metadata. The metadata can be users’ customization or personalization information, ratings, opinions, whatever.

3. A store of concepts: Concepts are very fluid: they don’t have owners, you don’t ask for permission to add to them, they have no formal structure or central piece of content, they can be organized in many ways, and they have no pre-defined set of qualities or attributes. Exactly the same can be said of Fluidinfo objects.

4. A platform for mashups: When a programmer makes a mashup, combining information from different sources to create information about something, where should that new information be stored? The usual answer today is to put the new information in a database, behind a new API, to document it, to get a server, to keep it running. In effect this is just making another hoop for future programmers to jump through to make an additional mashup. In Fluidinfo you can put the new information with the old—because objects don’t have owners. And that’s where it’s probably most valuable, because it’s then immediately available to be mashed up with other data on the same object, and search can target heterogeneous (i.e., mashed up) data on the same object.

5. A way of storing social graphs: Because users each have a Fluidinfo object associated with them, it is very easy to build social graphs. For example, user Andy might put an andy/i-follow tag onto the object for user Betty. If you have a few people doing that, interesting queries are then immediately possible—both within and across social networks.

6. A new way of organizing information: When we organize things, we are creating new information. Normally we store that new information elsewhere. When you can store it on the objects that are being organized, lots of nice things happen. I have an upcoming blog post that I’m tempted to title “Multiple simultaneous non-conflicting dynamic sharable organizations.” A bit of a mouthful, but nevertheless true.

You can also build all data structures from tags in Fluidinfo. They’re slower to use than data structures in a typical program, but where you lose in speed you gain in flexibility.

7. Something that frees us from APIs/UIs: APIs and UIs are usually regarded in a positive way: they make getting to information easy for programs and people. But they also control us. We can only do what they allow and what they anticipate. Tight limits are imposed on us in getting to our own data. Fluidinfo can change this: you can own your own data, you can always add data and customize, and you can directly search on anything you like.

8. A communication system: You can look at Fluidinfo objects as places for cooperating applications to exchange information. The information could be messages, jobs and results, etc. Nicholas Radcliffe, who has understood Fluidinfo for years, today found a new pleasing angle to look at it from, as a Twitter for data.

You could easily use a Fluidinfo object as a voting box, with some nice properties (e.g., retract or change your vote, verify that someone voted without being able to read their vote). And you can do more complex things, too.

9. An evolutionary data system: Fluidinfo allows reputation, trust, and convention to evolve. Its namespaces, tags, and users all have objects, and these give natural places to accumulate fitness information. Conventions will evolve for naming and tag values, just as they do for tags and hashtags. Selection pressure will take care of fixing ambiguities exactly to the extent that it’s important and worthwhile to fix them.

10. An alist on everything: One of the oddest moments ever in trying to explain Fluidinfo came when talking to Paul Graham. After at least 10 minutes of trying to find an angle for him, he finally said “oh, I get it. It’s an alist on everything.” I smiled, breathed a sigh of relief, and said yes. Well why didn’t you say so? replied Paul. Just goes to show you can never have too much background in computer science.