Passion and the creation of highly non-uniform value

Here, finally, are some thoughts on the creation of value. I don’t plan to do as good a job as the subject merits, but if I don’t take a rough stab at it, it’ll never happen.

Here, finally, are some thoughts on the creation of value. I don’t plan to do as good a job as the subject merits, but if I don’t take a rough stab at it, it’ll never happen.

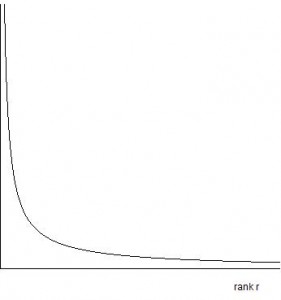

I’ll first explain what I mean by “the creation of highly non-uniform value”. I’m talking about ideas that create a lot of (monetary) value for a very small number of people. If you made a graph and on the X axis put all the people in the world, in sorted order of how much they make from an idea, and on the Y axis you put value they each receive, we’re talking about distributions that look like the image on the right.

In other words, a setting in which a very small number of people try to get extremely rich. I.e., startup founders, a few key employees, their investors, and their investors’ investors. BTW, I don’t want to talk about the moral side of this, if there is one. There’s nothing to stop the obscenely rich from giving their money away or doing other charitable things with it.

So let’s just accept that many startup founders, and (in theory) all venture investors, are interested in turning ideas into wealth distributions that look like the above.

I was partly beaten to the punch on this post by Paul Graham in his essay Why There Aren’t More Googles? Paul focused on VC caution, and with justification. But there’s another important part of the answer.

One of the most fascinating things I’ve heard in the last couple of years is an anecdote about the early Google. I wrote about it in an earlier article, The blind leading the blind:

…the Google guys were apparently running around search engine companies trying to sell their idea (vision? early startup?) for $1M. They couldn’t find a buyer. What an extraordinary lack of.. what? On the one hand you want to laugh at those idiot companies (and VCs) who couldn’t see the huge value. OK, maybe. But the more extraordinary thing is that Larry Page and Sergei Brin couldn’t see it either! That’s pretty amazing when you think about it. Even the entrepreneurs couldn’t see the enormous value. They somehow decided that $1M would be an acceptable deal. Talk about a lack of vision and belief.

So you can’t really blame the poor VCs or others who fail to invest. If the founding tech people can’t see the value and don’t believe, who else is going to?

I went on to talk about what seemed like it might be a necessary connection between risk and value.

After more thought, I’m now fairly convinced that I was on the right track in that post.

It seems to me that the degree to which a highly non-uniform wealth distribution can be created from an idea depends heavily on how non-obvious the value of the idea is.

If an idea is obviously valuable, I don’t think it can create highly non-uniform wealth. That’s not to say that it can’t create vast wealth, just that the distribution of that wealth will be more widely spread. Why is that the case? I think it’s true simply because the value will be apparent to many people, there will be multiple implementations, and the value created will be spread more widely. If the value of an idea is clear, others will be building it even as you do. You might all be very successful, but the distribution of created value will be more uniform.

Obviously it probably helps if an idea is hard to implement too, or if you have some other barrier to entry (e.g., patents) or create a barrier to adoption (e.g., users getting positive reinforcement from using the same implementation).

I don’t mean to say that an idea must be uniquely brilliant, or even new, to generate this kind of wealth distribution. But it needs to be the kind of proposition that many people look at and think “that’ll never work.” Even better if potential competitors continue to say that 6 months after launch and there’s only gradual adoption. Who can say when something is going to take off wildly? No-one. There are highly successful non-new ideas, like the iPod or YouTube. Their timing and implementation were somehow right. They created massive wealth (highly non-uniformly distributed in the case of YouTube), and yet many people wrote them off early on. It certainly wasn’t plain sailing for the YouTube founders – early adoption was extremely slow. Might Twitter, a pet favorite (go on, follow me), create massive value? Might Mahalo? Many people would have found that idea ludicrous 1-2 years ago – but that’s precisely the point. Google is certainly a good example – search was supposedly “done” in 1998 or so. We had Alta Vista, and it seemed great. Who would’ve put money into two guys building a search engine? Very few people.

If it had been obvious the Google guys were doing something immensely valuable, things would have been very different. But they traveled around to various companies (I don’t have this first hand, so I’m imagining), showing a demo of the product that would eventually create $100-150B in value. It wasn’t clear to anyone that there was anything like that value there. Apparently no-one thought it would be worth significantly more that $1M.

I’ve come to the rough conclusion that that sort of near-universal rejection might be necessary to create that sort of highly non-uniform wealth distribution.

There are important related lessons to be learned along these lines from books like The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and The Innovator’s Dilemma.

Now back to Paul’s question: Why aren’t there more Googles?

Part of the answer has to be that value is non-obvious. Given the above, I’d be willing to argue (over beer, anyway) that that’s almost by definition.

So if value is non-obvious, even to the founders, how on earth do things like this get created?

The answer is passion. If you don’t have entrepreneurs who are building things just from sheer driving passion, then hard projects that require serious energy, sacrifice, and risk-taking, simply wont be built.

As a corollary, big companies are unlikely to build these things – because management is constantly trying to assess value. That’s one reason to rue the demise of industrial research, and a reason to hope that cultures that encourage people to work on whatever they want (e.g., Google, Microsoft research) might be able to one day stumble across this kind of value.

This gets me to a recent posting by Tim Bray, which encourages people to work on things they care about.

It’s not enough just to have entrepreneurs who are trying to create value. As I’m trying to say, practically no-one can consistently and accurately predict where undiscovered value lies (some would argue that Marc Andreessen is an exception). If it were generally possible to do so, the world would be a very different place – the whole startup scene and venture/angel funding system would be different, supposing they even existed. Even if it looks like a VC or entrepreneur can infallibly put their finger on undiscovered value, they probably can’t. One-time successful VCs and entrepreneurs go on to attract disproportionately many great companies, employees, funding, etc., the next time round. You can’t properly separate their raw ability to see undiscovered value from the strong bias towards excellence in the opportunities they are later afforded. Successful entrepreneurs are often refreshingly and encouragingly frank about the role of luck in their success. They’re done. VCs are much less sanguine – they’re supposed to have natural talent, they’re trying to manufacture the impression that they know what they’re doing. They have to do that in order to get their limited partners to invest in their funds. For all their vaunted insight, roughly only 25% of VCs provide returns that are better than the market. The percentage generating huge returns will of course be much smaller, as in turn will be those doing so consistently. I reckon the whole thing’s a giant crap shoot. We may as well all admit it.

I have lots of other comments I could make about VCs, but I’ll restrict myself to just one as it connects back to Paul’s article.

VCs who claim to be interested in investing in the next Google cannot possibly have the next Google in their portfolio unless they have a company whose fundamental idea looks like it’s unlikely to pan out. That doesn’t mean VCs should invest in bad ideas. It means that unless VCs make bets on ideas that look really good – but which are e.g., clearly going to be hard to build, will need huge adoption to work, appear to be very risky long-shots, etc. – then they can’t be sitting on the next Google. It also doesn’t mean VCs must place big bets on stuff that’s highly risky. A few hundred thousand can go a long way in a frugal startup.

I think this is a fundamental tradeoff. You’ll very frequently hear VCs talk about how they’re looking for companies that are going to create massive value (non-uniformly distributed, naturally), with massive markets, etc. I think that’s pie in the sky posturing unless they’ve already invested in, or are willing to invest in, things that look very risky. That should be understood. And so a question to VCs from entrepreneurs and limited partners alike: if you claim to be aiming to make massive returns, where are your necessary correspondingly massively risky investments? Chances are you wont find any.

There is a movement in the startup investment world towards smaller funds that make smaller investments earlier. I believe this movement is unrelated to my claim about non-obviousness and highly non-uniform returns. The trend is fuelled by the realization that lots of web companies are getting going without the need for traditional levels of financing. If you don’t get in early with them, you’re not going to get in at all. A big fund can’t make (many) small investments, because their partners can’t monitor more than a handful of companies. So funds that want to play in this area are necessarily smaller. I think that makes a lot of sense. A perhaps unanticipated side effect of this is that things that look like they may be of less value end up getting small amounts of funding. But on the whole I don’t think there’s a conscious effort in that direction – investors are strongly driven to select the least risky investment opportunities from the huge number of deals they see. After all, their jobs are on the line. You can’t expect them to take big risks. But by the same token you should probably ignore any talk of “looking for the next Google”. They talk that way, but they don’t invest that way.

Finally, if you’re working on something that’s being widely rejected or whose value is being widely questioned, don’t lose heart (instead go read my earlier posting) and don’t waste your time talking to VCs. Unless they’re exceptional and serious about creating massive non-uniformly distributed value, and they understand what that involves, they certainly wont bite.

Instead, follow your passion. Build your dream and get it out there. Let the value take care of itself, supposing it’s even there. If you can’t predict value, you may as well do something you really enjoy.

Now I’m working hard to follow my own advice.

I had to learn all this the hard way. I spent much of 2008 on the road trying to get people to invest in Fluidinfo, without success. If you’re interested to know a little more, earlier tonight I wrote a Brief history of an idea to give context for this posting.

That’s it for now. Blogging is a luxury I can’t afford right now, not that I would presume to try to predict which way value lies.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.

November 10th, 2008 at 3:17 pm

I’m glad you are off to the races without the wasted overhead of fundraising. The “last Google” required different things for VCs to recognize it than you are ascribing to the problem. It required PhD candidates out of a particular lab at Stanford. It required killer angels like Bob Bozeman, Ron Conway, Andy Bechtolsheim, and others to invest first. And, it required the Series A to be done in 1998/9. Nonobviousness was by far secondary.

November 10th, 2008 at 4:17 pm

I’m glad you are off to the races without the wasted overhead of fundraising. The “last Google” required different things for VCs to recognize it than you are ascribing to the problem. It required PhD candidates out of a particular lab at Stanford. It required killer angels like Bob Bozeman, Ron Conway, Andy Bechtolsheim, and others to invest first. And, it required the Series A to be done in 1998/9. Nonobviousness was by far secondary.

November 10th, 2008 at 3:30 pm

Hi Scott!

I’m not sure if I understand you. Regarding Google, I’m only saying that at some early point no-one, including the founders, could see anything like the true value in what they were building. I certainly agree that it required multiple things to happen, as you list, before the potential value began to be apparent. But I wasn’t trying to describe the kinds of things that are necessary for the value to be recognizable to VCs.

In any case, thanks for commenting, and thanks for your encouragement and support. You were right about Eric! :-) But that would have been too early and the wrong path for me. Hopefully I’ll get there one day too.

Terry

November 10th, 2008 at 4:30 pm

Hi Scott!

I’m not sure if I understand you. Regarding Google, I’m only saying that at some early point no-one, including the founders, could see anything like the true value in what they were building. I certainly agree that it required multiple things to happen, as you list, before the potential value began to be apparent. But I wasn’t trying to describe the kinds of things that are necessary for the value to be recognizable to VCs.

In any case, thanks for commenting, and thanks for your encouragement and support. You were right about Eric! :-) But that would have been too early and the wrong path for me. Hopefully I’ll get there one day too.

Terry

November 10th, 2008 at 3:33 pm

BTW Scott, I recalled our London discussion about Powerset (and your fondness for frankness) last night as I was re-reading something I wrote earlier. I nearly mailed you with the link. Seeing as I’ve got your attention:

http://www.fluidinfo.com/terry/2007/11/02/powerset-hampered-by-limited-resources-oh-please/

November 10th, 2008 at 4:33 pm

BTW Scott, I recalled our London discussion about Powerset (and your fondness for frankness) last night as I was re-reading something I wrote earlier. I nearly mailed you with the link. Seeing as I’ve got your attention:

http://www.fluidinfo.com/terry/2007/11/02/powerset-hampered-by-limited-resources-oh-please/

November 13th, 2008 at 12:15 am

What a terrific article.

It remids me of an interview I saw with Larry David, co-founder of Seinfeld. This was well after Seinfeld (think Altavista) was the massive success.

Larry said that when he started writing his new series (think Google) he had no idea it would work (think Google trying to sell for $1 mill). It was format different enough to be risky.

I thought – wow, if a guy with so much trak record under his belt still feels all the risk, the risk never does go away.

The series (curb your enthusiasm) of course was a success.

Regards,

Kevin – Sydney Australia

November 13th, 2008 at 1:15 am

What a terrific article.

It remids me of an interview I saw with Larry David, co-founder of Seinfeld. This was well after Seinfeld (think Altavista) was the massive success.

Larry said that when he started writing his new series (think Google) he had no idea it would work (think Google trying to sell for $1 mill). It was format different enough to be risky.

I thought – wow, if a guy with so much trak record under his belt still feels all the risk, the risk never does go away.

The series (curb your enthusiasm) of course was a success.

Regards,

Kevin – Sydney Australia

November 13th, 2008 at 12:21 am

Hi Kevin

Thanks – that’s interesting. And thanks too for taking the time to comment!

Terry

November 13th, 2008 at 1:21 am

Hi Kevin

Thanks – that’s interesting. And thanks too for taking the time to comment!

Terry

November 14th, 2008 at 2:48 pm

Brilliant, absolutely fucking brilliant article. Thank you for sharing. Totally agreed on the BigCo not being able to produce a Google, because they won’t see the immediate value, and that’s what they want their resources devoted to: next Quarter, next FY, etc… Only incubated startups withing BigCo will potentially do it inside of a BigCo, and then the question is will BigCo let those startups live long enough to be valuable in the way you’re thinking… history tells us no.

November 14th, 2008 at 3:48 pm

Brilliant, absolutely fucking brilliant article. Thank you for sharing. Totally agreed on the BigCo not being able to produce a Google, because they won’t see the immediate value, and that’s what they want their resources devoted to: next Quarter, next FY, etc… Only incubated startups withing BigCo will potentially do it inside of a BigCo, and then the question is will BigCo let those startups live long enough to be valuable in the way you’re thinking… history tells us no.

November 14th, 2008 at 9:51 pm

Hi John

Thanks! :-)

Terry

November 14th, 2008 at 10:51 pm

Hi John

Thanks! :-)

Terry

December 6th, 2008 at 6:13 am

This is the one of the best articles I have read all year. Your logic is airtight, even dangerous for VC’s, and entrepreneurs alike. Your assertion that no one can accurately asses value is counter-intuitive, and yet so true. I am thrilled to have found an original, irreverent thinker that cuts his own swath through the jungle of ‘know-it-all’ VC’s and entrepreneurs that deny the role of random luck in their success. Will look forward to devouring the rest of your articles and seeing the alpha launch of your technology. Thanks again for a brilliantly-insightful read! Cheers,

Dan Hodgins

Vancouver Canada

Second-time entrepreneur and recent university graduate

December 6th, 2008 at 7:13 am

This is the one of the best articles I have read all year. Your logic is airtight, even dangerous for VC’s, and entrepreneurs alike. Your assertion that no one can accurately asses value is counter-intuitive, and yet so true. I am thrilled to have found an original, irreverent thinker that cuts his own swath through the jungle of ‘know-it-all’ VC’s and entrepreneurs that deny the role of random luck in their success. Will look forward to devouring the rest of your articles and seeing the alpha launch of your technology. Thanks again for a brilliantly-insightful read! Cheers,

Dan Hodgins

Vancouver Canada

Second-time entrepreneur and recent university graduate

December 6th, 2008 at 8:25 am

Hi Dan

Wow… thank you. What a nice way to wake up! Irreverent is the best praise. I’m glad that comes through, I spend most of my time thinking silly things and making stupid jokes that no-one understands…

Thanks again,

Terry

December 6th, 2008 at 9:25 am

Hi Dan

Wow… thank you. What a nice way to wake up! Irreverent is the best praise. I’m glad that comes through, I spend most of my time thinking silly things and making stupid jokes that no-one understands…

Thanks again,

Terry

December 7th, 2008 at 11:55 pm

Yay! This article thrills and motivates me. Thank you!

December 8th, 2008 at 12:55 am

Yay! This article thrills and motivates me. Thank you!

December 8th, 2008 at 12:00 am

HI Manuel

That’s great, thanks. And thanks for reading the other posts too, I just read your two other comments.

Terry

December 8th, 2008 at 1:00 am

HI Manuel

That’s great, thanks. And thanks for reading the other posts too, I just read your two other comments.

Terry

January 26th, 2009 at 1:08 pm

Terry,

Hi, I just found this post and this blog from the business leaders at another blog, Anyway, WOW, is all I have to say, That was a really good article and I needed to read that.

The article really hit home with me, Thanks !

Joseph

January 26th, 2009 at 2:08 pm

Terry,

Hi, I just found this post and this blog from the business leaders at another blog, Anyway, WOW, is all I have to say, That was a really good article and I needed to read that.

The article really hit home with me, Thanks !

Joseph

June 1st, 2009 at 2:43 pm

[…] fluidinfo Blog Archive Passion and the creation of highly non Posted by root 15 minutes ago (http://www.fluidinfo.com) It seems to me that the degree to which a highly non uniform wealth distribution can be series think google he had no idea it would work think google trying to sell for 1 mill and thanks too for taking the time to comment terry fluidinfo is powered by wor Discuss | Bury | News | fluidinfo Blog Archive Passion and the creation of highly non […]

October 1st, 2009 at 7:23 am

I have to run out for some exercise now but your thought flow blogging style is mixing well with some of my own ideas:

The Creation of Value

Notional Framework for Monetization Web2010

I specifically enjoyed the fact that Larry and Sergei had no idea what their concept was worth. The idea probably was probably worth less than one million at that time. The implementation and monetization has been of course, PRICELESS.

March 24th, 2010 at 1:13 pm

David Fisher once wrote “What often characterizes visionaries is their lack of vision. It's a popular idea that people of genius see farther and clearer than other people, but perhaps the truth is actually the opposite. Visionaries often don’t notice the enormous and obvious impediments to realizing their technological dreams – roadblocks apparent to more practical people”.

I think he was really onto something, as are you in this post. If we knew what it looked like (ie the big winners) all of this would be a no-brainer. I started in VC working for Bill Hambrecht at H&Q VC in San Francisco. My first week on the job he said to me that — in the 20 years he had been investing in technology companies (about 400 of them) — he had come to realize that, as often as not, his biggest winners initially looked like they would fail, and those he was sure had the most promise, did fail.

This business isn't about following trends (or herds), but it's also not about hunting “Thunder Lizzards'. It's about investing in people that are passionate about transforming something, changing it, doing something better than it has ever been done before. Back those often enough, and abnormal distributions will follow.

March 24th, 2010 at 4:12 pm

Hi Jim – thanks for reading :-)

That's all very interesting. I wish I had more experience to be better able to judge whether my thoughts hold water. I'll be interested to talk to you further about all this… the 2nd & 3rd paragraphs above are great (though I had to go look up what a Thunder Lizard is). I think this is the first time I've seen some of what I think acknowleged as being an explicit part of an investment thesis: 1) that you can't put your finger on value, and 2) that you should invest in passion. I know it'll never be that simple, but to have those two as more-or-less guiding principles is, I think, sensible. The whole argument is that if you don't, the abnormal distributions wont follow.

Thanks for taking the time. I find all this fascinating.

March 24th, 2010 at 7:13 pm

David Fisher once wrote “What often characterizes visionaries is their lack of vision. It's a popular idea that people of genius see farther and clearer than other people, but perhaps the truth is actually the opposite. Visionaries often don’t notice the enormous and obvious impediments to realizing their technological dreams – roadblocks apparent to more practical people”.

I think he was really onto something, as are you in this post. If we knew what it looked like (ie the big winners) all of this would be a no-brainer. I started in VC working for Bill Hambrecht at H&Q VC in San Francisco. My first week on the job he said to me that — in the 20 years he had been investing in technology companies (about 400 of them) — he had come to realize that, as often as not, his biggest winners initially looked like they would fail, and those he was sure had the most promise, did fail.

This business isn't about following trends (or herds), but it's also not about hunting “Thunder Lizzards'. It's about investing in people that are passionate about transforming something, changing it, doing something better than it has ever been done before. Back those often enough, and abnormal distributions will follow.

March 24th, 2010 at 10:12 pm

Hi Jim – thanks for reading :-)

That's all very interesting. I wish I had more experience to be better able to judge whether my thoughts hold water. I'll be interested to talk to you further about all this… the 2nd & 3rd paragraphs above are great (though I had to go look up what a Thunder Lizard is). I think this is the first time I've seen some of what I think acknowleged as being an explicit part of an investment thesis: 1) that you can't put your finger on value, and 2) that you should invest in passion. I know it'll never be that simple, but to have those two as more-or-less guiding principles is, I think, sensible. The whole argument is that if you don't, the abnormal distributions wont follow.

Thanks for taking the time. I find all this fascinating.

May 28th, 2010 at 2:09 am

[…] spent a lot of time pondering the link between obviousness, the creation of value, and passion. I often try to get people to read that […]