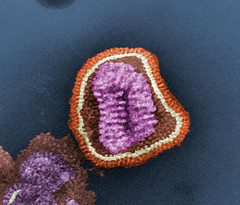

Here are some more thoughts on the (now official) influenza pandemic.

Here are some more thoughts on the (now official) influenza pandemic.

I would like again to emphasize that I’m not an authority and I’m not trying to pass myself off as one.

I’ve already been accused of deliberate fear-mongering. That’s the opposite of my purpose. On the contrary, it’s important to stay calm and there are good reasons for doing so. If you don’t want to know a bit of history and to have some sense of things that have happened in previous pandemics, then you don’t have to read what follows. There’s no harm in staying calm via not knowing. On the other hand, there is harm in being gripped by fear due to ignorance.

If you do read, try to keep in mind that the main point here is that you shouldn’t be overwhelmed by fear or begin to panic. There’s no reason to. Plus it will only make things worse.

On the subject of being an authority and fear-mongering, after I wrote up the first set of thoughts I was invited to be a guest commentator on a radio show. I declined. It feels very irresponsible to say anything about influenza given that I am not an expert and don’t even work in the field anymore, but OTOH it feels irresponsible to remain totally silent given that I know at least some historical things fairly well.

To illustrate the conflict: On April 26 it seemed crystal clear to me that the virus was going worldwide. You only had to have seen the Google map that I twittered about the day before to see that it was going to be all over the place in days. But I didn’t want to point that out, and when I was asked I told the asker to be his own judge. I linked to a map showing Mexico and the US earlier and said “hopefully we wont have to zoom out” – trying to get people to consider that we would probably soon have to zoom out.

So I think I’ve been quite restrained. This post is also restrained. As I said above, there are good reasons not to sensationalize things or to create the impression that people should panic.

So here we go again, a few more thoughts as they come to mind. These are things that I find interesting, with a few scattered opinions (all of which are just guesses). There’s no real structure to this post.

The WHO have announced today that we’re officially in a pandemic. That doesn’t really mean much, but it’s good to have a candid and early declaration – part of the problem historically has been slowness to even admit there’s a problem. The WHO didn’t even exist in 1918.

In case you don’t know, there’s pretty good evidence that humans have been fighting influenza for thousands of years.

The most interesting thing to me in reading about the 1918 pandemic is the social impact of the disease.

One thing to make clear is that the current pandemic is not the 1918 pandemic. I tend to agree with those who say that a pandemic of that nature could not take place today – but note that people, perhaps especially scientists – would have said that at all times prior to and after 1918. We often under-estimate the forces of nature and over-estimate our own knowledge and level of control.

BTW, something like 75% of people who died during World War 1 did so because of the flu pandemic, which didn’t really take off until November of 1918. Amazing.

As I mentioned in my earlier post, under normal circumstances (even in a pandemic), flu doesn’t kill you. It leaves you susceptible to opportunistic follow-on disease. The good news is that we are vastly more informed now than we were in 1918 about the nature of infectious diseases. For example, we know a lot about pneumonia, which we did not in 1918. See the moving story of the amazing Oswald Avery, who dedicated his life to the disease and along the way fingered DNA as the vehicle of genetic inheritance – and never won a Nobel prize.

So the care of people who have been struck down by flu is going to be much more informed this time around. And it will probably be better in practice too. I put it that way because odd societal things happen in a pandemic. I hesitate to go into detail, because some people will assume that things that happened way back when will necessarily happen again this time around.

One of those things is that medical systems get overrun by the sick. Plus, doctors and nurses understandably decide that their jobs have become too dangerous and they stop showing up for work. So there can be a sharp drop-off in the availability of medical help.

So much so that there were reports of doctors and nurses being held hostage in houses in 1918. I.e., if you could get a doctor to visit to attend to your family, the situation was so dire you might consider pulling a gun on him/her and suggesting they make themselves comfortable for the duration.

The problem is not so much that many people are dying, it’s that a much larger number are simultaneously extremely ill and that panic grips them and everyone else. Roughly 30% of all people caught the 1918 flu. I have another post I may write up on that. Normal (epidemic) flu catches 10-15% of people in any give year.

Many of our systems are engineered to provide just-in-time resources, to cut the fat in order to maximize profitability, etc. That means that we’re closer to collapse that would seem apparent. How many days of fresh food are there on hand in a major city?

None of this is meant to be alarmist. But the reality is that alarming things have happened in the past.

Most interesting and revealing to me is that our cherished notions of politeness, of our generosity, our goodwill towards our neighbors, etc., can all go out the window pretty quickly. I’ve long held that all those things are the merest veneer on our underlying biological / evolutionary reality. We’re very fond of the ideas that we’re somehow no longer primates, that we’re not really the product of billions of years of evolutionary history, that somehow the last centuries of vaunted rationality have put paid to all those primitive lower impulses. I think that’s completely wrong. Behavior during a full-scale pandemic is one of the things that makes that very clear.

In a pandemic, if things get ugly, you can expect to see all manner of anti-social behavior. If you read John Barry’s book The Great Influenza or Crosby’s America’s Forgotten Pandemic you’ll get some graphic illustrations.

If I had a supply of tamiflu (which I don’t), I wouldn’t tell anyone. That’s deliberately anti-social. Ask yourself: What would you do if you had kids who were still healthy and your neighbor called you in desperation to tell you that his/her kids seemed to have come down with influenza? Get out your family’s tamiflu supply and hand it over? Lie? What if they knew you had it and you refused to give it or share? What if your neighbor’s kid died and yours never even got the flu? What kind of relationship would be left after the pandemic had passed?

This may all seem a bit extreme and deliberately provocative of me, and yet those sorts of dilemmas (sans tamiflu, naturally) were commonplace in 1918. As you might expect, they don’t always get resolved in ways that accord well with our preferred beliefs about our own natures in easier times. Crosby speculates that the reason the pandemic of 1918 is “forgotten” is due largely to the fact that it coincided with the war, and that people were generally exhausted and dispirited and wanting to move on. I’d speculate further that people en masse frequently behaved in ways that they weren’t proud of, and wanted to forget about it and act as if it hadn’t happened ASAP. That’s just a guess, of course.

In any case, if there’s a full-blown pandemic, societal structures that we take for granted are going to be hugely transformed. Medical services, emergency services, food supply, child care and education, job absenteeism, large numbers of the people who would normally be in charge of things coming down sick and being unable to do their normal jobs, etc. All sorts of things are impacted and lots of them are interconnected. The system breaks down in many unanticipated ways as all sorts of things that “could never happen” are all happening at once.

You might think I’m fear-mongering here, but I’m not. In fact I’m refraining from going into detail. Go read John Barry’s book, or any of the others, and see for yourself.

The important thing to remember in all this is that we are no longer in 1918. BTW, there were also influenza pandemics in 1957 (killing just a couple of million people) and 1968 (killing a mere million).

Apart from the fact that we’ve advanced hugely in medical terms, we are also much better connected. I can sit in the safety of my apartment in Barcelona and broadcast calming information like this blog post to thousands of people. We are better informed. We know that panic and fear greatly compound the impact of a pandemic. They feed on one another and prolong the systemic societal collapse. Because we can communicate so easily via the internet – provided our ISPs stay online – we can help keep each other calm. That’s an important advantage.

So my guess is that this wave isn’t going to be so bad, certainly not in terms of mortality. One thing to keep in mind though is that the virus isn’t going away. It will likely enjoy the Southern hemisphere winter, and we’ll see it again next Northern hemisphere winter. And yes, those are guesses. Because influenza is a single-stranded RNA virus it mutates rapidly (you don’t get the copy protection of a double strand). So this is the beginning, not the end, even if the pandemic fizzles out in the short term. It will be back – probably in less virulent form – but by then we’ll also have a good leg up on potential vaccines, and we’ll also know it’s coming.

OK, I’ll stop there for now. I have tons of other things I could write now that I’m warmed up. You can follow me on Twitter if you like, though I doubt I’ll be saying much about influenza.

If you truly believe I’m fear mongering, please send me an email or leave your email address in the comments. I’ll send you mail with some truly shocking and frightening stuff, or maybe fax you a few pages from some books. Believe me, it gets a lot nastier than anything I’ve described. Things are not that bad, certainly not yet. We’re not in 1918 anymore

So, stay calm, and do the simple things to keep yourself relatively safe. If everyone follows instructions like those, the virus wont have a chance to spread the way it could otherwise. That may sound like pat concluding advice, but there’s actually a lot to it – the epidemiology of infectious disease – in part the mathematics of infection – can be hugely altered depending on the behavior the typical individual. Following basic hygiene and getting your kids to too will make a big difference. There’s no denying that this is going to get worse before it gets better, but we can each do our part to minimize its opportunities.