Here, finally, are some thoughts on the creation of value. I don’t plan to do as good a job as the subject merits, but if I don’t take a rough stab at it, it’ll never happen.

Here, finally, are some thoughts on the creation of value. I don’t plan to do as good a job as the subject merits, but if I don’t take a rough stab at it, it’ll never happen.

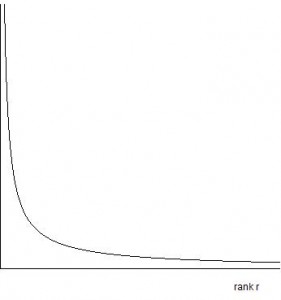

I’ll first explain what I mean by “the creation of highly non-uniform value”. I’m talking about ideas that create a lot of (monetary) value for a very small number of people. If you made a graph and on the X axis put all the people in the world, in sorted order of how much they make from an idea, and on the Y axis you put value they each receive, we’re talking about distributions that look like the image on the right.

In other words, a setting in which a very small number of people try to get extremely rich. I.e., startup founders, a few key employees, their investors, and their investors’ investors. BTW, I don’t want to talk about the moral side of this, if there is one. There’s nothing to stop the obscenely rich from giving their money away or doing other charitable things with it.

So let’s just accept that many startup founders, and (in theory) all venture investors, are interested in turning ideas into wealth distributions that look like the above.

I was partly beaten to the punch on this post by Paul Graham in his essay Why There Aren’t More Googles? Paul focused on VC caution, and with justification. But there’s another important part of the answer.

One of the most fascinating things I’ve heard in the last couple of years is an anecdote about the early Google. I wrote about it in an earlier article, The blind leading the blind:

…the Google guys were apparently running around search engine companies trying to sell their idea (vision? early startup?) for $1M. They couldn’t find a buyer. What an extraordinary lack of.. what? On the one hand you want to laugh at those idiot companies (and VCs) who couldn’t see the huge value. OK, maybe. But the more extraordinary thing is that Larry Page and Sergei Brin couldn’t see it either! That’s pretty amazing when you think about it. Even the entrepreneurs couldn’t see the enormous value. They somehow decided that $1M would be an acceptable deal. Talk about a lack of vision and belief.

So you can’t really blame the poor VCs or others who fail to invest. If the founding tech people can’t see the value and don’t believe, who else is going to?

I went on to talk about what seemed like it might be a necessary connection between risk and value.

After more thought, I’m now fairly convinced that I was on the right track in that post.

It seems to me that the degree to which a highly non-uniform wealth distribution can be created from an idea depends heavily on how non-obvious the value of the idea is.

If an idea is obviously valuable, I don’t think it can create highly non-uniform wealth. That’s not to say that it can’t create vast wealth, just that the distribution of that wealth will be more widely spread. Why is that the case? I think it’s true simply because the value will be apparent to many people, there will be multiple implementations, and the value created will be spread more widely. If the value of an idea is clear, others will be building it even as you do. You might all be very successful, but the distribution of created value will be more uniform.

Obviously it probably helps if an idea is hard to implement too, or if you have some other barrier to entry (e.g., patents) or create a barrier to adoption (e.g., users getting positive reinforcement from using the same implementation).

I don’t mean to say that an idea must be uniquely brilliant, or even new, to generate this kind of wealth distribution. But it needs to be the kind of proposition that many people look at and think “that’ll never work.” Even better if potential competitors continue to say that 6 months after launch and there’s only gradual adoption. Who can say when something is going to take off wildly? No-one. There are highly successful non-new ideas, like the iPod or YouTube. Their timing and implementation were somehow right. They created massive wealth (highly non-uniformly distributed in the case of YouTube), and yet many people wrote them off early on. It certainly wasn’t plain sailing for the YouTube founders – early adoption was extremely slow. Might Twitter, a pet favorite (go on, follow me), create massive value? Might Mahalo? Many people would have found that idea ludicrous 1-2 years ago – but that’s precisely the point. Google is certainly a good example – search was supposedly “done” in 1998 or so. We had Alta Vista, and it seemed great. Who would’ve put money into two guys building a search engine? Very few people.

If it had been obvious the Google guys were doing something immensely valuable, things would have been very different. But they traveled around to various companies (I don’t have this first hand, so I’m imagining), showing a demo of the product that would eventually create $100-150B in value. It wasn’t clear to anyone that there was anything like that value there. Apparently no-one thought it would be worth significantly more that $1M.

I’ve come to the rough conclusion that that sort of near-universal rejection might be necessary to create that sort of highly non-uniform wealth distribution.

There are important related lessons to be learned along these lines from books like The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and The Innovator’s Dilemma.

Now back to Paul’s question: Why aren’t there more Googles?

Part of the answer has to be that value is non-obvious. Given the above, I’d be willing to argue (over beer, anyway) that that’s almost by definition.

So if value is non-obvious, even to the founders, how on earth do things like this get created?

The answer is passion. If you don’t have entrepreneurs who are building things just from sheer driving passion, then hard projects that require serious energy, sacrifice, and risk-taking, simply wont be built.

As a corollary, big companies are unlikely to build these things – because management is constantly trying to assess value. That’s one reason to rue the demise of industrial research, and a reason to hope that cultures that encourage people to work on whatever they want (e.g., Google, Microsoft research) might be able to one day stumble across this kind of value.

This gets me to a recent posting by Tim Bray, which encourages people to work on things they care about.

It’s not enough just to have entrepreneurs who are trying to create value. As I’m trying to say, practically no-one can consistently and accurately predict where undiscovered value lies (some would argue that Marc Andreessen is an exception). If it were generally possible to do so, the world would be a very different place – the whole startup scene and venture/angel funding system would be different, supposing they even existed. Even if it looks like a VC or entrepreneur can infallibly put their finger on undiscovered value, they probably can’t. One-time successful VCs and entrepreneurs go on to attract disproportionately many great companies, employees, funding, etc., the next time round. You can’t properly separate their raw ability to see undiscovered value from the strong bias towards excellence in the opportunities they are later afforded. Successful entrepreneurs are often refreshingly and encouragingly frank about the role of luck in their success. They’re done. VCs are much less sanguine – they’re supposed to have natural talent, they’re trying to manufacture the impression that they know what they’re doing. They have to do that in order to get their limited partners to invest in their funds. For all their vaunted insight, roughly only 25% of VCs provide returns that are better than the market. The percentage generating huge returns will of course be much smaller, as in turn will be those doing so consistently. I reckon the whole thing’s a giant crap shoot. We may as well all admit it.

I have lots of other comments I could make about VCs, but I’ll restrict myself to just one as it connects back to Paul’s article.

VCs who claim to be interested in investing in the next Google cannot possibly have the next Google in their portfolio unless they have a company whose fundamental idea looks like it’s unlikely to pan out. That doesn’t mean VCs should invest in bad ideas. It means that unless VCs make bets on ideas that look really good – but which are e.g., clearly going to be hard to build, will need huge adoption to work, appear to be very risky long-shots, etc. – then they can’t be sitting on the next Google. It also doesn’t mean VCs must place big bets on stuff that’s highly risky. A few hundred thousand can go a long way in a frugal startup.

I think this is a fundamental tradeoff. You’ll very frequently hear VCs talk about how they’re looking for companies that are going to create massive value (non-uniformly distributed, naturally), with massive markets, etc. I think that’s pie in the sky posturing unless they’ve already invested in, or are willing to invest in, things that look very risky. That should be understood. And so a question to VCs from entrepreneurs and limited partners alike: if you claim to be aiming to make massive returns, where are your necessary correspondingly massively risky investments? Chances are you wont find any.

There is a movement in the startup investment world towards smaller funds that make smaller investments earlier. I believe this movement is unrelated to my claim about non-obviousness and highly non-uniform returns. The trend is fuelled by the realization that lots of web companies are getting going without the need for traditional levels of financing. If you don’t get in early with them, you’re not going to get in at all. A big fund can’t make (many) small investments, because their partners can’t monitor more than a handful of companies. So funds that want to play in this area are necessarily smaller. I think that makes a lot of sense. A perhaps unanticipated side effect of this is that things that look like they may be of less value end up getting small amounts of funding. But on the whole I don’t think there’s a conscious effort in that direction – investors are strongly driven to select the least risky investment opportunities from the huge number of deals they see. After all, their jobs are on the line. You can’t expect them to take big risks. But by the same token you should probably ignore any talk of “looking for the next Google”. They talk that way, but they don’t invest that way.

Finally, if you’re working on something that’s being widely rejected or whose value is being widely questioned, don’t lose heart (instead go read my earlier posting) and don’t waste your time talking to VCs. Unless they’re exceptional and serious about creating massive non-uniformly distributed value, and they understand what that involves, they certainly wont bite.

Instead, follow your passion. Build your dream and get it out there. Let the value take care of itself, supposing it’s even there. If you can’t predict value, you may as well do something you really enjoy.

Now I’m working hard to follow my own advice.

I had to learn all this the hard way. I spent much of 2008 on the road trying to get people to invest in Fluidinfo, without success. If you’re interested to know a little more, earlier tonight I wrote a Brief history of an idea to give context for this posting.

That’s it for now. Blogging is a luxury I can’t afford right now, not that I would presume to try to predict which way value lies.

I’m a big fan of

I’m a big fan of