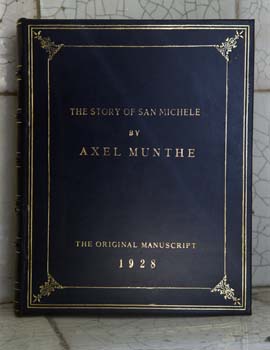

La Storia di San Michele

Axel Munthe

In 1928, Axel Munthe, a Swedish physician living on the isle of Capri, published The Story of San Michele. Munthe’s villa on the slopes of Mount Barbarossa stands on a site chosen almost two thousand years earlier by the emperor Tiberius, who from tiny Capri held sway over the entire Roman empire. Extraordinarily beautiful, the island passed at various times through the hands of the Greeks, the Romans (Caesar Augustus was captivated), the Dutchy of Naples, the Saracens, the Longobards, the Normans, the Angevins, the Aragonese, the Spanish, and the Bourbons.

On completing his medical studies, Munthe was the youngest physician in Europe. The Story of San Michele describes his time in Paris and Rome, his years as the physician to the Swedish Royal family and later his years as private physician to the queen of Sweden, who had also taken a liking to Capri. Written in English, The Story of San Michele, which remains in print, was an instant success, becoming the best-selling non-fiction book in the U.S. in 1930. Munthe’s novel approach to medicine and the book’s mixture of adventure, treasure, and royalty continue to inspire. The Story of San Michele was the mysterious target of one Henry Arthur Harrington, a petty thief who crisscrossed the UK, stealing 1,321 copies from second-hand bookstores before his eventual arrest in 1982. Even in 2003, Munthe’s contributions are the subject of learned attention: the Second International Symposium on Axel Munthe’s life and work will be held in Sweden tomorrow (September 13).

With the rapid success of The Story of San Michele, the book was a natural target for would-be translators. Editions in several languages were soon completed. Given its origin, it was odd that such a popular book was not more quickly translated into Italian.

Patricia Volterra

Living in Florence, Patricia Volterra was fascinated by the book and was eager for her husband Gualti to read it too. A minor obstacle: Gualti did not speak English. Undeterred, Volterra decided to translate the book into Italian. She wrote to John Murray, the publisher, requesting permission. To her surprise, she received a reply directly from Munthe. From Volterra’s diary, Munthe told her that:

the book had already been translated into several languages and was selling like wildfire. To date he had refused offers for it to be translated into Italian as, he wrote, this language, when written, was apt to become too flowery and overloaded and that he had written the book in an extremely simple style which he wished to retain. However, he continued, he suggested I should translate the last chapter, which he considered the most difficult, and send it to him to the Torre Matterita at Anacapri. He would then let me know whether he thought he could permit me to translate the rest.

Volterra sent off her translation of the final chapter and spent several weeks waiting for an answer. Finally her manuscript was returned “with an extremely complimentary letter from Munthe, telling me to proceed to do the rest.” Later she wrote that at that time nothing seemed impossible to her but that now she wouldn’t have even considered the translation.

While working on the translation, she had lunch with Munthe in Rome when Gualti, an Italian concert pianist, was playing at the Augusteum. Munthe was staying at Villa Svezia, the Queen of Sweden’s residence on the Via Aldovrandi. When Munthe saw her he exclaimed ‘My goodness, how old are you?’ She: ‘Twenty three.’ He: ‘And you are translating San Michele!’ Munthe was over 70 at the time.

Volterra sent the work to an Italian publisher, Mondadori, who refused her. “Their great loss,” she wrote. Another, Treves, accepted. Munthe “had decreed that the entire royalties should go to the Society for the Protection of Animals in Naples.” Volterra was to sell her translation for whatever she could get for it. This amounted to the equivalent of 50 pounds sterling for 8 months work.

Later that spring, Volterra traveled to Capri. In a horse-drawn cab they drove to Anacapri where they visited San Michele. From there on foot through the olives to the Torre di Materita to have lunch with Munthe. A variety of his dogs scampered round his heels as he showed them the old tower which was then his home. They had a vegetarian lunch served by Rosina, so affectionately mentioned by Munthe in his book.

The Volterra translation ran quickly into 35 editions and was still selling well when she left Italy in 1938. Mussolini was so impressed by La Storia di San Michele that he passed a law prohibiting the shooting of migratory birds on Capri.

Volterra saw Munthe one final time, in Jermyn Street, London. Munthe died in 1949, leaving the villa of San Michele to Sweden. Owned today by the Swedish Munthe Foundation, it is home to an ornithological research center and is open to the public.

[Continued in part two, "Bob Arno".]

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.

August 8th, 2011 at 4:31 am

[…] in 2003, this is the 2nd part of the story of a remarkable connection. You'll need to read part one for the set […]

October 19th, 2011 at 7:28 am

Intriguing story. Strange really – I never realised what a popular book it was til I read your blog (which I stumbled upon whilst googling away while sick in bed this arvo). I bought the book in about 1987 and have never met anyone else who had read it. I was so interested in the book that I went to the villa when I was on Capri in 1991. But I still have not finished Godel, Escher and Bach…

Jane (way back – Syd Uni days)

July 24th, 2012 at 4:00 am

Jane!!? Wow, funny, I just re-read the above and noticed there was a comment…. I’d not seen it. It’s funny, I tried googling you only a few weeks ago, but came up with nothing. I’m terry at jon dot es if you want to email.